Luther King’s thinking and activism was based on three basic principles: There is a fundamental

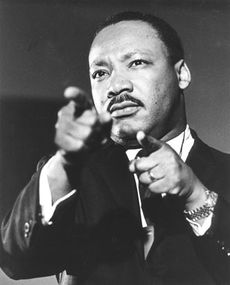

Martin Luther King Jr. (1929-1968) was born into the home of a reverend in Atlanta, Georgia. In 1954, at the age of 25, he became the pastor of a Baptist church in Montgomery, Alabama, and in 1955 he received a Ph.D. in systematic theology from Boston University.

In his dissertation he compared the conception of God in the respective works of philosophers and theologians Paul Tillich and Henry Nelson Wieman. In spite of the differences he pointed out in the theology of the two thinkers, King ultimately accused both of holding an impersonal view of God – conceiving of a God with whom a living, prayerful relationship was not possible.

King stood for nonviolent protest, inspired by Gandhi’s struggle in India. His work as a civil rights proponent began in Montgomery in 1955, where he headed a mass boycott of the town’s buses, prompted by the arrest of Rosa Parks for not giving up her seat for to white man. In 1957 he became the president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), which worked to equip black churches for nonviolent civil rights protest.

The heyday of King and the civil rights movement was the first half of the 1960s, when a number of important marches took place. It was on the occasion of the march to Washington D.C. in 1963 that King delivered his famous “I have a dream” speech. Martin Luther King received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964 for his work against racial discrimination.

Over the following years, he carried on his work and became engaged in the resistance against the Vietnam War and against poverty. In 1968 he was shot in Memphis, Tennessee, while visiting the town to support the black sanitation workers in their struggle for higher pay and better work conditions.

King was introduced to personalist thought during his studies at Boston University, which was at the time the stronghold of American personalism. He wrote a dissertation on personalism and subscribed to its thinking:

“This personal idealism remains today my basic philosophical position. Personalism’s insistence that only personality – finite and infinite – is ultimately real strengthened me in two convictions: it gave me metaphysical and philosophical grounding for the idea of a personal God, and it gave me a metaphysical basis for the dignity and worth of all human personality.”

When Martin Luther King held his famous speech, “I have a dream,” on August 28, 1963 on the stairs of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington D.C. this was in a fundamental way a personalist dream. It was a dream that had sprouted in his childhood, found its philosophical form at Boston University, and unfolded in the American civil rights movement.